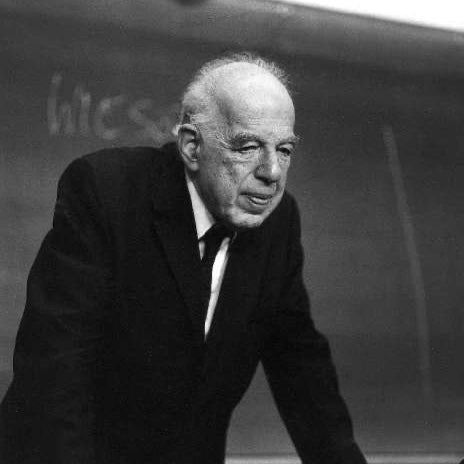

How has the Discipline of Art History Changed Since Gombrich?

The discipline of art history is one that has, in many ways, changed drastically over the last 73 years since Sir E. H. Gombrich wrote his 1950 The Story of Art. In that time, the world, especially the Western world, which, as Elkins argues in his 2002 Stories of Art, is almost the home of art history[1], has changed drastically, with many long-held views disappearing and altering, and questions being asked as to what exactly constitutes art history. In that time, we have seen the rise of interest in the study of items such as clothing, design and more abstract art, many of which were not included in Gombrich’s book. Other ways in which the discipline of art history has changed can be seen in the growing interest in the inclusion of works of art both depicting and by people from previously overlooked backgrounds, due to factors such as their race, sexuality or gender.

A well-known example of the study of design being treated as the study of art and architecture can be seen in the designs of William Morris, namely the wallpaper and items of furniture. Red House is an example of an Arts and Crafts building in Bexleyheath, formerly Kent, designed by William Morris and Philip Webb, and constructed between 1859 and 1860. Gombrich’s Story of Art, although mentioning Morris a few times, does not go into much detail about the artistic skill of his interior designing, instead drawing on the importance of him on the inspiration for Art Nouveau[2]. The house was created as a response to the nineteenth century art critic John Ruskin’s complaints about the mass-produced materials being used in Victorian housebuilding, and the Pre-Raphaelites, whose interests were in the revival of many mediaeval aspects of art and design. In the last few years especially, there has been a greater interest and appreciation of Morris’ wallpapers as art, as can be seen in the exhibitions that have been staged concerning his wallpapers[3]. Morris was forced to leave the house in 1865 due to numerous factors, and it ended up being owned by many people. In 1985 the first tour groups entered, and by 2003 it was owned by the National Trust[4], which has further increased interest in the interior of the building. Gombrich describes Morris’ work more as propaganda than art[5], again showing the difference between art and Morris’ work that was felt by art historians at the time. Much of Morris’ work, especially his wallpapers and carpets, have gone on to be very popular in many English homes, reflecting the interest that many have in him, and the high prices that many pay, at least £100 for a metre of roll[6], show just how popular it has become, not only for its aesthetic purposes, but also as a status symbol.

Morris and Webb, Red House, 1859, Bexleyheath, Kent

When being interviewed by Michael Squire about his interpretation of classical sculpture, English sculptor Marc Quinn agreed with Squire when he called his 2004 Alison Lapper Pregnant ‘part of a larger rethinking about what the classical is’[7]. Quinn said that he was inspired by the damaged sculptures of Antiquity, such as the Venus de Milo and the Elgin Marbles, both of which have parts missing, giving the appearance of deformity. Alison Lapper MBE was born in 1965, and suffers from a congenital condition known as phocomelia, which causes her to have no arms, as well as shortened legs. From birth, Lapper was made aware of her condition, with a cleaner in the maternity ward exclaiming unknowingly to Lapper’s mother: ‘It’s [Lapper] a horrible looking thing. The nurses say she’ll die in a day or two, or else be a cabbage for the rest of her life.’[8]. Quinn, whose work often touches on underrepresented and controversial subjects, such as his 1991-present Self, made out of 10 pints of his own blood, reproduced roughly every five years, and the 2009 Buck and Allanah, which shows two naked transgender porn stars standing in a pose reminiscent of the Early Renaissance depictions of Adam and Eve, was keen to show her in a way that did not treat her like a performer in a freak show[9], instead he preferred to depict her as what she is, a human. When the sculpture was unveiled on the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square in September 2005 alongside great Britons, such as Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson, King George IV and John, 1st Earl Jellico, then Mayor of London Ken Livingston remarked ‘Alison’s life is a struggle over much greater difficulties than the men who are celebrated here’[10], quite a compliment when compared to those greats, showing how views towards people have changed. The Fourth Plinth is used for many similar works, for example Samson Kambalu’s 2022 Antelope, a sculpture based off the 1914 photograph of pan-Africanist John Chilembwe and European missionary John Chorley, and Teresa Margolles’ upcoming 2024 850 Improntas, which is made up of 850 casts of transgender people’s faces from around the world. Although this statue was made in an era when the mocking of people with disabilities was more commonplace, it ‘brought disability to the forefront of the public consciousness’[11]. The fact that a sculpture of a woman like Lapper, whose disability would not have been included in any of the works of art spoken about by Gombrich 54 years prior, was able to be exhibited in one of the most prominent locations for public sculpture in the UK shows just how far the ideas of what and who should be shown in statues have changed, the public’s changing views about the discussion of disability.

Marc Quinn, Alison Lapper Pregnant, 2004, marble, 355cm x 180.5cm x 260cm, temporarily on the Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London

The way in which female artists and architects are viewed is another way in which the discipline of art history has changed in the last 70 years. An example is the seventeenth century Italian Baroque paintress, Artemisia Gentileschi, whose work, and the work of any other female artist, is completely ignored by Gombrich in The Story of Art, despite it being widely acknowledged as a staple in the learning of history of art[12]. Despite occasional interest over the centuries, such as Roberto Longhi in 1916 describing her as ‘the only woman in Italy who ever knew about painting, colouring, drawing and other fundimentals’[13], it was not until the 1970s, with the publication of American art historian Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, that there was more of a feminist interest in Gentileschi. In the foreword to Eve Straussman-Phlanzer’s Violence and Virtue: Artemisia’s Judith Slaying Holofernes, Douglas Druick argues that it was due to Nochlin’s essay that art historians and scholars were prompted to further “integrate women artists into the history of art and culture.”[14] Gentilieschi’s rape in 1611 at the hands of painter Agostino Tassi is viewed by many to have provided her with a prompt for the subject of a number of her paintings, namely that of the numerous depictions of Judith Slaying Holofernes. Whilst the scene is of a Biblical nature, coming from Judith 10:11-13:10a, Gentileschi was known to use her own figure as a model for the figure of Judith, perhaps as a way of expressing her private and repressed rage[15]. Despite having several of her works attributed to Caravaggio, she has re-entered the public eye, most recently being reattributed to a piece in the Royal Collection, Susannah and the Elders.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes, c. 1612-1613, oil on canvas, 146.5cm x 108cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The changing attitudes towards what exactly constitutes ‘art’, gender, sexuality, disability and other aspects mean that the discipline of art history has changed greatly since the publication of The Story of Art in 1950. The, in some cases, desire, and in others, need, to include subjects that have previously been overlooked has meant that more emphasis has been put on these works, and greater time spent studying them. There is still greater change, such as the art of the Global South and East, as well as much indigenous art, that has been looked at, all of which largely ignored in The Story of Art.

[1]James Elkins, Stories of Art (New York/London: Routledge, 2002), 140

[2] E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (London: Phaidon, 1950, 16th edition reprinted 2020), 135

[3] “The Art of Wallpaper – Morris & Co”, Dovecot Studios, accessed 24th October 2023, https://www.dovecotstudios.com/exhibitions/the-art-of-wallpaper-morris-co

[4] Malcom Youngs, The Later Owners of the Red House (Kent: Friends of Red House, 2011), 59-60

[5] Gombrich, The Story of Art, 135

[6] “Pure Willow Boughs”, Morris & Co, accessed 24th October 2023, https://www.morrisandco.sandersondesigngroup.com/product/wallpaper/dmpu216022/

[7] Michael Squire, Marc Quinn, “’Casual Classicism’: In Conversation with Marc Quinn”, International Journal of the Classical Tradition, Vol. 26, No. 2 (June 2019), 221

[8] “Beauty unseen, unsung”, The Guardian, 3rd September 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/sep/03/art1, extracted from Alison Lapper and Guy Feldman, My Life In My Hands (London: Simon & Schuster, 2005)

[9] ibid

[10] Charlotte Higgins, “Sculpture’s unveiling is pregnant with meaning”, The Guardian, 16th September 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/sep/16/arts.artsnews

[11] Charles Josefson, “The Fourth Plinth: raising the issue of disability”, Disability Arts Online, 7th August 2017, https://www.disabilityarts.online/magazine/opinion/fourth-plinth-raising-issue-disability/

[12] “The Story of Art”, Phaidon, accessed 24th October 2023, https://www.phaidon.com/store/art/the-story-of-art-9780714833552/

[13] Roberto Longhi, Gentileschi, Padre e Figlia (L’Arte, XIX, 1916)

[14] Douglas Druick, in Eve Straussman-Phlanzer, Violence and Virtue: Artemisia’s Judith Slaying Holofernes (Chicago, Illinios: Art Institute of Chicago: 2013), foreword

[15] Patricia Phillippy, Painting Women: Cosmetics, Canvases, and Early Modern Culture (USA: John Hopkins University Press: 2006), 75

This article was originally written for a university essay in October 2023, titled: How has the discipline of art history changed since Gombrich wrote the following sentence? “In the chapters which follow I shall discuss the history of art, that is the history of building, of picture-making and of statue-making.” E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (London: Phaidon, 1950), 18.